Basic Types of Systems Projects

CHAPTER SYNOPSIS

This chapter presents a brief discussion of the most common types of applications found in most firms, and the cases which follow (Chapter 23) illustrate the environments and issues facing firms in various types of industries. The application discussions and the cases illustrate the variety of implementations as they appear in different types of firms.

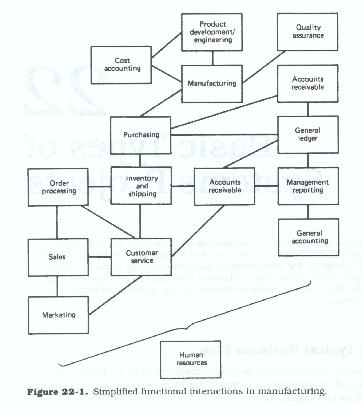

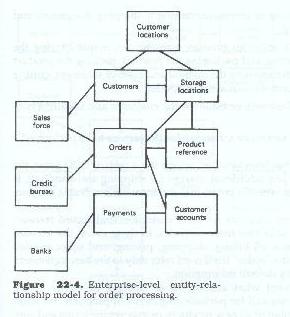

The Typical Business Flow

In order to understand the general characteristics of the most commonly addressed applications, it is important to understand the typical business flow (see Figure 22.1).

Most organizational activity can be traced to some origination in the marketing and sales functions of the firm. These superfunctions include the functions of

It is here that customers are identified and sales are made. These sales are received by the firm in the form of orders for the firm's products and/or services. The incoming orders are edited, validated, credit checked, and placed in the firm's processing stream.

If the orders are for products, the products are taken from inventory, shipped, and invoiced. As product is taken from inventory, the inventory records are updated and the quantities on hand are then checked against minimum or optimum stock levels. If the quantities have dropped below these levels, orders are placed for replacement stock.

Once invoiced, the orders become part of the firm's receivable accounts, or moneys due. It is for these satisfied orders that bills and statements are processed, and against which payments are received.

The replacement of inventory products, either by purchase or by manufacture, causes the firm to place orders with other firms. These orders become part of the firm's payable accounts, or moneys owed.

When replacement stock is needed, purchase or manufacturing orders are cut, vendors for stock or materials are contacted and orders placed, receiving orders are prepared, and inspection areas are notified.

In some cases the firm's business calls for it to receive and manage moneys for its customers. The transactions associated with this activity are recorded in a separate set of accounts, called customer accounts (in banks, called demand deposit accounts, savings accounts, etc.). When the firm's business calls for it to receive and hold a customer's property, accounts are also set up to record each physical asset transaction.

Transactions associated with financial aspects of the firm's business, both internal and for customers--moneys due, owed, received, paid out, retained as profit, and property received, disbursed, and retained--are recorded in a structured set of individually titled financial records called general ledgers.

The firm must also recruit, hire, and manage people as employees of the company, develop and maintain records on those employees, and compensate those employees for services rendered. The recording of these records and of compensation information is handled by a complex set of functions known as human resources (or by their individual function titles: personnel and payroll).

On a periodic basis, the firm and its auditors must prepare financial reports, perform inventory counts, and issue financial statements to various agencies and to the firm's owners.

It is important for the analyst to be familiar with the general aspects of each of these types of functions and the data and processing which are associated with them. It is equally important that the analyst recognize that although most companies have similar functions, applications, and systems, they are not identical from company to company, or even from company division to company division. Their differences have been shaped by the individual company's

These factors, singly or in combination, result in the requirement that each analysis and development project make no assumptions with respect to the processing required, steps within those processes, or the data which drive the project. Each project must be assumed to be new and unique.

The industry descriptions highlight the differences in basic company functions and processes; however, across industries many similar functions exist as well. Given their similarity across industries, it should not be surprising that these functions are either administrative or managerial in nature, although they are all greatly affected by the particular type of business of the firm and by the operational systems which service them.

In order to understand the functional differences, the analyst should first have an understanding of each of these basic functions. Although there are many functions within the typical organization, there is a limited set which appear in some form in every organization, whether the firm engages in direct product manufacture, acts as agent for the sale of products made by others, or delivers a service.

Among these functions are

The functional descriptions which follow are general overviews intended to familiarize the analyst with the terminology and basic activities and processes of these common functions. The descriptions are, of necessity, very general and incomplete but do reflect many of a firms functional activities, the general flow of information, and the complexity and importance of the function as well as its relationships and interactions with and impact on other functional areas of the firm.

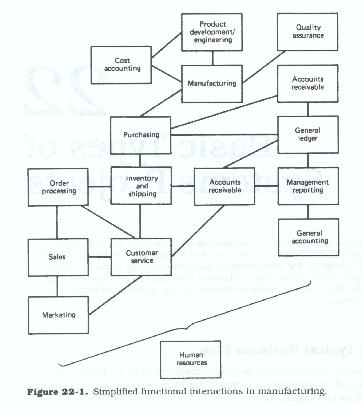

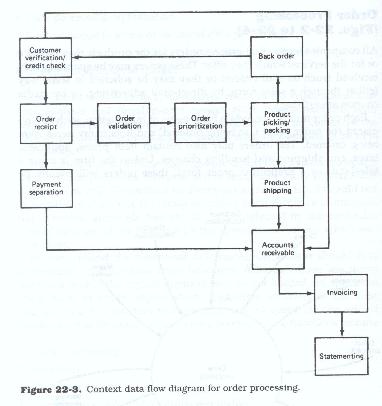

Order Processing (Figures 22.2 to 22.4)

All companies receive and process orders for the products they produce or for the services which they offer. These orders may be spontaneously received (such as mail orders) or they may be solicited in some way (either through a sales force, by direct mail advertising, or by media coupon advertising).

Each order must have certain basic items of information, including: who placed the order, what was being ordered, and how many were being ordered. The orders may also contain item prices, applicable taxes, and shipping and handling charges. Unless the firm is using a sales staff or a preprinted order form, these orders will usually be free form, less than complete, and may contain inaccuracies and discrepancies. In some cases, the item ordered may not even be one the company sells. In others, it may be for items which the company no longer offers. The item description may be complete and accurate or may be vague and incomplete.

Orders may be accompanied by payment which might be complete and accurate, overpaid, or underpaid. In many cases the orders may be cash on delivery (COD), may have a credit card number, or may ask for later billing.

Each order must be examined, edited, corrected where necessary, and entered into the pending order files of the firm for later satisfaction. This edit and correction process usually includes verification of item description, price, discounts taken or offered, taxes, all additional fees and charges, and all extensions and totals, as well as addition of the company item number where necessary.

In addition the order must be checked to ensure that the customer name and address are properly entered, that any shipping or billing information is complete and accurate, and that any sales or commission information is recorded for that order. Any priorities associated with the order, or for any item on the order, must be noted, and any complete ship, partial ship, or delayed ship instructions should also be noted.

If the order contains a credit card payment or post-shipment billing, the order is usually sent to the credit check area where any credit card authorizations are obtained or a credit check may be done on the customer. If payment was by check, the firm may elect to delay shipment until the check clears the bank.

Once the order has been accepted, the processing of the order varies with the firm, and, it is highly dependent upon whether the order is for goods or services. This processing is industry, company, and product specific, but, generally speaking, it involves one of the following:

Once the order has been satisfied, unless it is a cash or COD order, the order, along with any additional charges for shipping and handling, is sent to accounting where it enters into the accounts receivable processing streams.

Many firms open accounts for their customers and record transactions for buys or sells into these accounts. In these cases, the account application contains all billing, shipping, pricing, and other needed information, and the "order" itself need only refer to the base agreement and "override" any default information.

Other firms accept what are known as standing or master orders. Standing orders may call for periodic shipments of products, for shipments of a set number of all new products, or may set the terms and conditions for future orders which may be issued against it. These standing orders are usually placed either (a) to save paperwork on future orders, (b) to take advantage of volume discounts, or (c) to lock in current prices for future deliveries.

In some cases, where the customer has multiple locations, the customer may place master orders which specify the total quantity, price, central billing information, and the quantities that are to be shipped to each location. For some master orders, each location is billed separately and the central office is sent a consolidated statement.

Orders may specify that the product be shipped to the ordering customer's own locations, shipped to client locations, or stored by the company for later shipment.

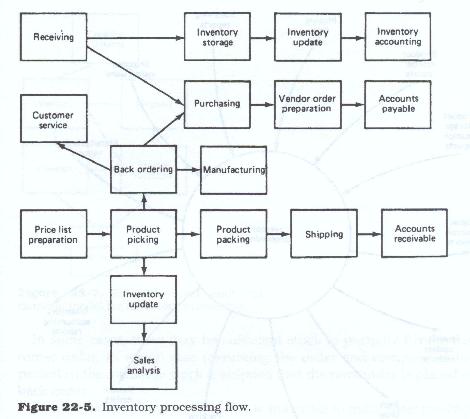

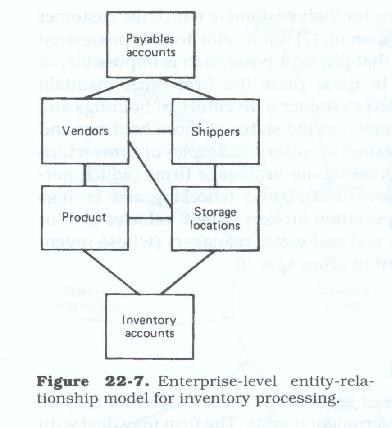

Inventory (Figures 22.5 to 22.7)

Those firms which offer products for sale and which either manufacture the product themselves, wholesale the product (buy from the manufacture and then sell to retailers), or act as agents or consignment sellers usually sell from inventory.

The inventory may be on premises, in separate warehouses, external to the firm (held by another), or of such a nature that the product itself is stationary and only ownership changes hands (e.g., houses, buildings, land, natural resources, etc.).

Regardless of where the physical product is kept, the products are assets of the firm. Thus their sale must be accounted for, and the firm must keep accurate records of transfers into and from stock or of how much is left to sell (in the case of depletable resources).

Each transaction to and from inventory (the total product available for sale) is recorded on an ongoing basis. Periodically the firm will check the recorded quantities on hand against the actual quantities on hand (a physical inventory count). In many cases variance reports are issued and discrepancies accounted for. In all cases the recorded inventory is changed to reflect the actual quantities on hand (since that is actually what is there).

During day-to-day order and shipment processing, the removals from inventory are recorded and the remaining quantity is checked against some predetermined quantity (usually called a "reorder point"). In some cases, stock cannot be replenished (such as one-of-a-kind items); in this case, once the last item is sold, the records are marked inactive.

For those items which can be replenished, when the reorder point is reached, a restock, repurchase, or re-manufacture order is issued. These reorder points are calculated by a variety of methods and usually reflect estimated sales volumes, time to restock, "safety limits," manufacturing times, and a number of other variables.

If the firm miscalculates its sales volumes or there are delays in obtaining new stock, orders for depleted items may be "back ordered." Back ordering simply means that the order is set aside and placed in a file, usually by item, until such time as new stock is obtained. In these cases, the customer is normally notified of the back-order condition and given an estimate of when the stock will be available.

In some cases, there may be sufficient stock to partially fill the customer order, in which case (assuming the order and company policy permit it) the available stock is shipped and the remainder is placed on back order.

Manufacturing firms which use raw materials to make their products or which use purchased components which are assembled into the company's product have complex systems in place to ensure that sufficient materials are on hand for manufacturing. These systems are usually called materials requirements planning (MRP) systems, and work from product bills of materials and work schedules. MRP systems attempt to work backward from the manufacturing processes and use lead times, purchasing times, inspection times, etc., to automatically determine when and how much material must be ordered to ensure that the company's production lines are continually supplied.

Since inventory of finished product, "work-in-process" product (product which is partially manufactured), and raw materials represent an investment of funds, most firms attempt to maintain a balance between having too much stock and not enough stock so that manufacturing will not stop or customer orders go unfilled. Inventory systems work in conjunction with sales analysis systems, manufacturing systems, purchasing systems, and materials management systems to ensure that this balance is maintained. Periodic reports are usually needed to determine slow- or fast-moving items, stock turnover, cost of inventory, and funds planning for new stock purchases.

Some firms buy and sell items for their customers which the customer may either

In these cases the firm must maintain accounts which keep track of the customer's inventory of holdings and periodically report to the customer on the status of those holdings and on details of all transactions against inventory. Examples of firms which use this type of inventory processing are brokerage firms (which normally hold their customers' securities), banks (checking and savings accounts), shipping and transportation brokers (where vehicles and/or cargo are constantly moving), and real estate managers (whose inventory is buildings and apartment or office space).

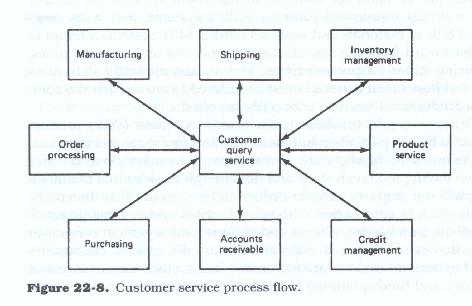

Customer Service (Figures 22.8 and 22.9)

All firms deal with customers of some type. These customers may be individuals, other firms, or governmental units. The firm may deal with the customer directly (over the phone or in person) or indirectly (by mail or other communication media).

These customer dealings, aside from straight sales, usually require either resolving some problem, providing some information, or providing other than normal service to the client. To handle these types of dealings, most firms maintain customer information files on (a) all customers or (b) selected customers. These files are used to maintain information on customers; their preferences, idiosyncrasies, likes, and dislikes; special handling requests; or more normally their transaction histories.

These files must be available when the customer calls or communicates for information, with a problem, or with a special request. Firms which extend credit to customers maintain credit information in these files along with transaction and payment histories.

Firms which maintain open accounts for their customers (ongoing accounts where the customer's transactions are recorded) must maintain the details of each transaction against those accounts and be able to tie the accounts to the customer's non-account information (i.e., credit, residence, demographic, billing, and shipping information, etc.).

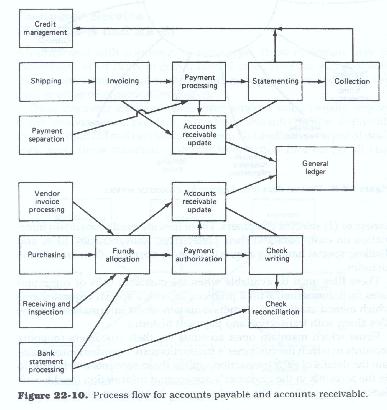

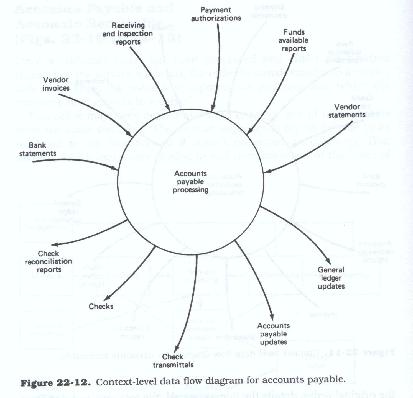

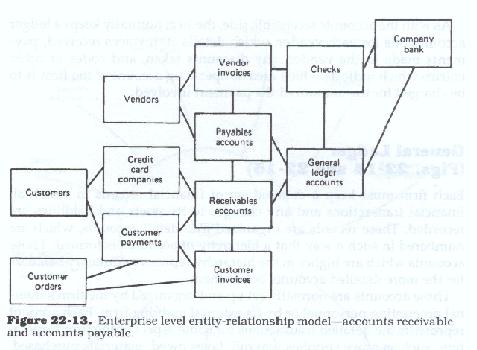

Accounts Payable and Accounts Receivable (Figures 22.10 to 22.13)

Once a customer order has been processed and either the product shipped or the service rendered, the order is transformed into a receivable item. That is, the order now represents a payment due, which the company now expects to receive.

This order may have been an isolated order or one of many orders from the same customer. The normal sequence is for an invoice to be rendered to the customer (if it wasn't presented upon delivery). That invoice, which looks very similar to and contains many of the items of the original order, details the items covered, the total amount due from the customer (including fees and charges), and payment terms.

Traditionally the customer will have 30 days to pay, although some terms call for payment at month end and others offer discounts for early payment. At the 30-day point, or at month end, all outstanding invoices, along with any payments received, or amounts due or credited to the customer for overpayments or returns, are summarized on a customer statement. These statements normally list all invoices closed since the last statement and all open (unpaid) invoices.

The statement may further break out open invoices into an "aged" listing, beginning with invoices over 90 days old, followed by invoices that are 60 to 90 days old, 30 to 60 days old, and under 30 days old.

Part of the accounts receivable processing includes receipt and application of payments. When making payments, customers are asked to indicate in some way which invoices are being paid. If the customer does so, the payments are applied to the indicated items. If not, they are normally applied to all open items starting with the oldest items first and working back to current items. This cascading effect of payment application usually results in partial payments being applied to some invoices.

All firms which maintain open accounts in this manner also maintain a set of ledger accounts, usually one for each customer where ongoing records of invoice and payment history are recorded. As payments are received and items are closed, the payments are routed to the various other company accounts in any one of a variety of ways and in accordance with how the company's general ledger system has been defined.

All firms purchase supplies, materials, and services from outside firms or individuals. They may be for product manufacture, office needs, or a variety of services. These purchases are transacted by issuing orders to vendors. Once the goods, materials, or services have been received, inspected, or otherwise accepted, the firm will receive the vendor's invoice, which becomes a payable item for the company. That is, it represents moneys which it owes to someone else. The same types of terms and conditions which govern the invoices which the company issues for its products apply to the invoices it receives.

Accounts Payable processing normally requires that the invoices be segregated into those which offer discounts and those which do not, and those which have been authorized for payment (the goods or services delivered and accepted) and those that have not yet been authorized (because the goods or services have not yet been delivered or accepted, or because of some dispute with the vendor).

Based upon a variety of factors, including availability of funds, the firm will prioritize the invoices and issue payments for them (either in full or in part). These payments may be in the form of checks or some other funds transfer mechanism.

For each check that is drafted, a record is kept which contains its number, amount, date, payee, and account codes. Each check issued in this manner is printed on a report or kept in automated files. When the bank statements and the corresponding canceled checks are received, they are reconciled with the records which the firm kept of its issued checks.

As with the accounts receivable side, the firm normally keeps a ledger account, one for each vendor, which details all invoices received, payments made to the vendor, any discounts taken, and codes or other entries which indicate which area or operating account of the firm is to be charged for the amount of the payment involved.

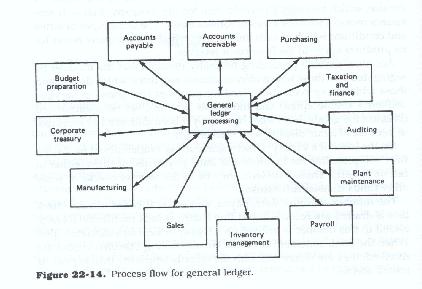

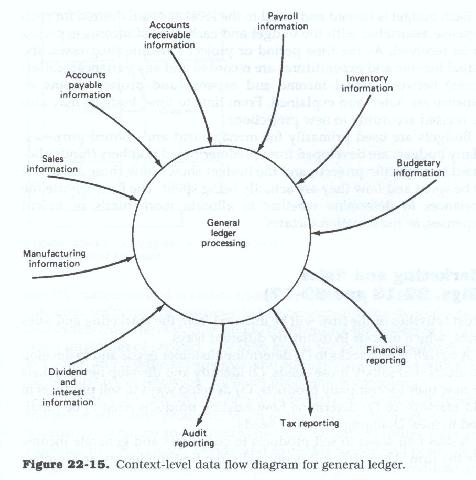

General Ledger (Figures 22.14 and 22.15)

Each firm must keep a detailed set of financial records in which all financial transactions and any changes to its assets and liabilities are recorded. These records are organized into detail accounts, which are numbered in such a way that a hierarchy of accounts is formed. Those accounts which are higher in the hierarchy represent summary balances for the more detailed accounts below them.

These accounts are normally set up and organized by the firm's internal accounting personnel or by its external auditing firm. Each account represents the detailed transactions for some aspect of the firm's operation, such as office supplies, payroll, taxes owed, materials purchased, goods sold, etc.

There are normally detail accounts for every type of asset and liability of the firm. Most firms use a double-entry method of bookkeeping, where each entry is recorded twice, once as a debit (amount owed, subtracted, or removed) and once as an offsetting credit (amount received or added).

Thus, if a payment is made to a vendor, a credit entry will be made to the vendor's account record and a debit entry made to the cash account. Still other entries will be made to the various internal accounts which will be "charges' for the payment against their operating budgets.

Most firms develop one or more detail and summary budgets which are used to monitor income and expenditures. These budgets are prepared for a period ranging from a week to a year or more. They may be organizational unit budgets for administrative purposes, project-specific budgets for development projects, manufacturing budgets, sales budgets, etc.

Each budget is named and listed to the level of detail desired for each expense associated with the budget and each item of income expected to be received. As the time period or project schedule progresses, the actual income and expenditures are recorded and any variances (differences) between actual income and expense and project income or expense are noted and explained. From time to time, budgets may also be revised based on new projections.

Budgets are used primarily for management and control purposes. Many budgets are developed from predetermined numbers (funds allocated to a specific project), and the budget shows how those funds are to be spent and how they are actually being spent. The firm can use the variances to determine whether to allocate more funds or to cut expenses, as the situation dictates.

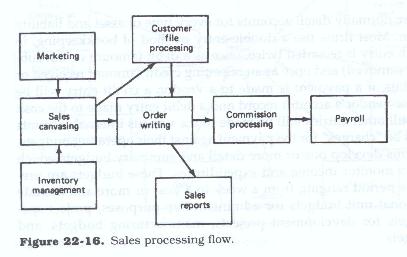

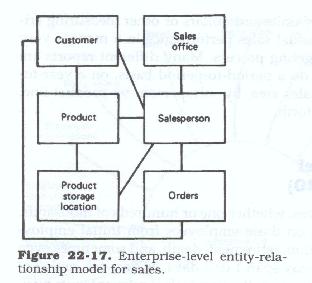

Marketing and Sales (Figures 22.16 and 22.17)

Most activities of the firm will be initiated from the marketing and sales units, which operate in distinctly different ways.

A marketing unit seeks

A sales unit seeks to sell products to customers and generate income for the firm. The sales unit is normally the first to identify and contact specific customers and is responsible for introducing the product to the customer, inducing the customer to buy or carry the firm's products; to take orders from the customer; and to try to induce the customer to carry larger quantities of product. The sales unit is the primary customer contact point, and it is the salespeople who normally are charged with making the first try at resolving customer problems or complaints.

Marketing units conduct surveys of potential customers, and develop and test market new products. Much of the work in the marketing area is statistical in nature and is used to develop customer profiles, sales and economic trends, industry trends, etc. Marketing will normally be charged with determining the sales price of any product introduced and the way in which it is to be presented to the customer. Marketing in many cases determines the level of quality to be built into the product.

Sales units are concerned with actual sales, developing sales projections and estimates, and monitoring actual sales against those projections. It is normally the sales unit which provides sales figures to manufacturing, which in turn adjusts production and purchasing schedules.

Sales also presents to management its estimates of the level of revenues which can reasonably be expected; these estimates in turn are used by management to determine the amount of money it will have to spend or borrow to fund operations.

The success of any firm is highly dependent on the success of its marketing and sales organizations.

As orders are generated, commission amounts are determined and allocated to the sales staff. These figures are then routed to payroll for compensation purposes. In applicable cases, sales reports also provide the basic information for any licensing or royalty payments which may be due on the products sold.

Sales estimates, in terms of units and dollars or other measuring criteria, are compared to the actual sales performance in a manner very similar to the financial budgeting process. Many different reports are generated which compare sales on a period-to-period basis, on a year-to-date basis, by product, by sales area, by salesperson, by product line, against competition, etc.

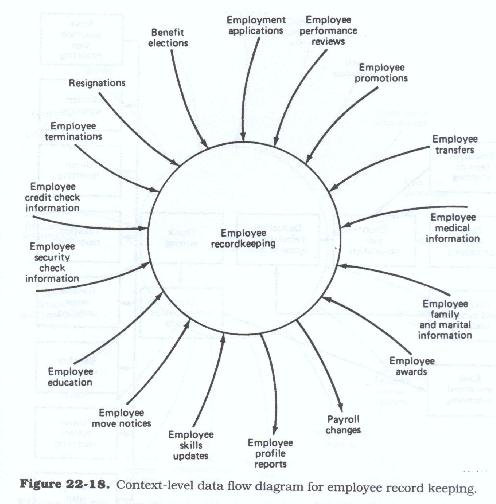

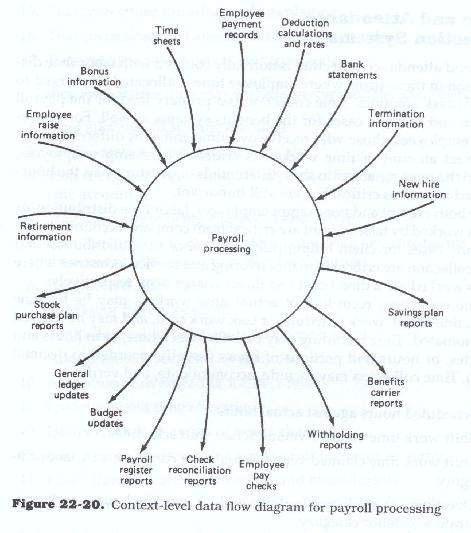

Payroll and Personnel (Figures 22.18 to 22.20)

All companies have employees, whether one or hundreds of thousands. The firm maintains records on these employees from initial employment application to termination, retirement, death, and sometimes even beyond that. These records may span 1 or 2 days, or decades and contain all employee information which the firm feels is relevant to its business. This information may include

Although the firm may acquire any information about the employee which is needed for employment purposes or for general background information, there are very strict regulations as to what it may do with that information, and how and when it may disclose it. Aside from product information, company strategic planning, and executive-decision making information, employee information is the most sensitive and by far the most strictly regulated. If the firm has any data security procedures in place, they are likely to be in the human resources area. The firm is more likely to be open to legal proceedings because of its personnel practices than from any other activity in which it engages. Many firms have more systems in place for human resources than for any other unit, and these systems tend to be among the oldest in the firm's systems portfolio.

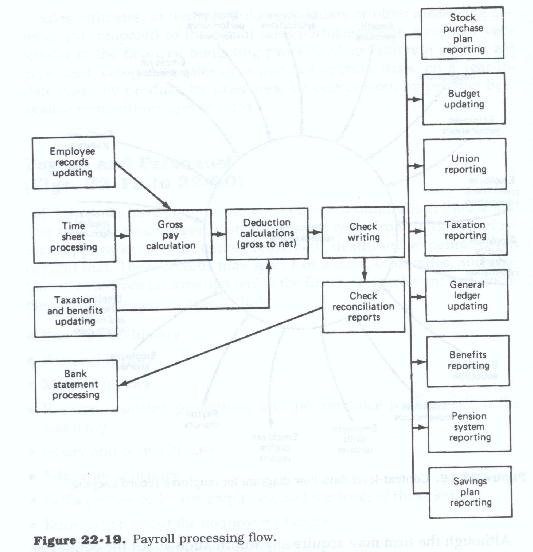

The payroll and compensation systems receive input from time sheets, commission reports, bonus reports, etc., and generate paychecks. All moneys due the employee are totaled, and a gross pay amount is generated. All tax and other deductions are computed, and a net amount is determined which is then paid to the employee.

Depending upon the number and variety of payment methods, the number and variety of the deductions, the number of locations where the employees work, and the taxing authorities for which money must be withheld, these payroll computation programs can be among the most complex the firm has. They are also among the most unstable, in that benefits and other deduction information, as well as taxation information and rules, change very frequently.

As the payroll checks are being cut, reports related to budgeting, taxes withheld, and benefits and insurance provided are generated and sent to many areas of the firm, e. g., accounts payable, finance, and general ledger. The moneys withheld for these deductions are placed in accounts for payment to the government and for payment of various other benefits. Moneys are set aside during each payroll cycle for pension purposes, for employee stock purchase plans, for employee savings plans, etc.

As with accounts payable, check registers are printed for later use in check reconciliation systems. All employee detail deduction information and year-to-date information is maintained for end-of-year tax reporting and for year-end statements. The information is also sent to finance for inclusion in the firm's quarterly and annual financial statements.

Time and Attendance Collection Systems

Time and Attendance collection is normally coupled with Labor Time Distribution in those firms where employee time is allocated or charged to specific task accounts. Time collection is a primary feed for the payroll system and in some cases for the benefits systems as well. For nonexempt employees, those who receive overtime and shift differential pay the exact amount of time worked is critical. For exempt employees, those who are not subject to shift differentials or overtime pay the hours worked are not as critical but still important.

For both exempt and non-exempt employees, labor time distribution, or hours worked by task account are critical from company accounting, and in may cases for client billing purposes.

Labor time distribution and time collection are critical in manufacturing and service industries where hours worked are a direct cost and direct charge items respectively.

Time collection, recording of actual time worked, may be by time clock, time sheet, work schedule, task work card, and may be manual or automated. Time recording may be actual clock time, or in hours and minutes, or hours and portions of hours (usually recorded in decimal form).

Time collection may include, accommodate and verify:

Labor time distribution may include, accomodate and verify

Labor time allocation and time collection may use separate forms in which case collection of both time and labor time distribution may be accompanied by additional processes designed to reconcile differences between time reported on the time collection forms as opposed to time reported on the labor time distribution forms.

Automation of Routine Request for Action Forms

Within any given firm there are a myriad of different forms each designed for a specific reason. Most are designed for collection of information or to request an action, or approval of proposed actions by others. Automated Request for Action forms may:

Obviously transition of these forms to an electronic form may require accommodation of these items. One of the more difficult aspects of automating these kinds of forms is the routing of these forms to the various management and operational reviewers and approvers. Electronic review and approval may be:

Electronic routing of forms for review and approval or comment must allow for:

A Professional's Guide to Systems Analysis, Second Edition

Written by Martin E. Modell

Copyright © 2007 Martin E. Modell

All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Except as permitted under United States Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means, or stored in a data base or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the author.