The Interview And Other Data Gathering Methods

CHAPTER SYNOPSIS

The interview is the primary technique for information gathering during the systems analysis phases of a development project. It is a skill which must be mastered by every analyst. The interviewing skills of the analyst determine what information is gathered, and the quality and depth of that information. Interviewing, observation, and research are the primary tools of the analyst.

This chapter provides a discussion of the interview and its importance, interview guidelines, and guidelines on interview documentation.

What Is an Interview?

A definition

An interview is "a formal face-to-face meeting, especially, one arranged for the assessment of the qualifications of an applicant, as for employment or admission.... A conversation, as one conducted by a reporter, in which facts, or statements are elicited from another." (The American Heritage Dictionary, Second College Edition)

The interview is the primary technique for information gathering during the systems analysis phases of a development project. It is a skill which must be mastered by every analyst. The interviewing skills of the analyst determine what information is gathered, and the quality and depth of that information. Interviewing, observation, and research are the primary tools of the analyst.

The interview is a specific form of meeting or conference, and is usually limited to two persons, the interviewer and the interviewee. In special circumstances there may be more than one interviewer or more than one interviewee in attendance. In these cases there should still be one primary interviewer and one primary interviewee.

Types of Interviews

During the analysis process, interviews are conducted for a variety of purposes and with a variety of goals in mind. An interview can be conducted at various times within the process for

Interviewing Components

The interview process itself consists of a number of parts.

What Are the Goals of the Interview?

At each level, each phase, and with each interviewee, an interview may be conducted to:

Interviewing Guidelines

Given these various phases and the variety of goals of an interview, the importance of a properly conducted interview should be self-evident. Since each interview is in fact a personal exchange of information between two personalities, a set of guidelines for the interviewer should be established to ensure that nothing interferes with the stated goal, i.e., gathering complete, accurate information. The interview is not an adversary relationship; instead it should be a conversation. Above all it is a process, and like most processes it has certain rules and guidelines which should be followed.

Dos and Don'ts of Interviewing

The rules of interviewing are similar to the rules which govern most human interactions and to the rules which govern most investigative and problem-solving processes. In effect they can be called the rules of the game.

Who to Interview

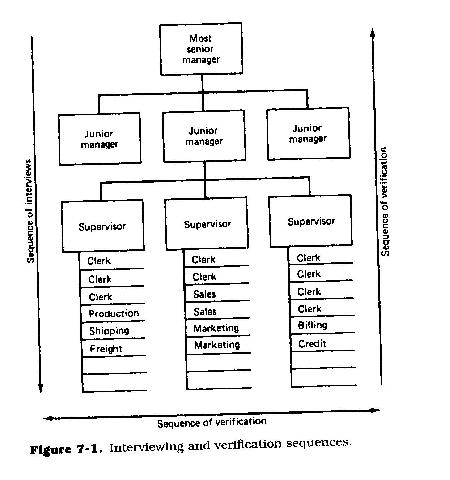

One of the analyst's first and most important tasks during the data gathering phase of the analysis process, is to determine who has to be interviewed. This includes selecting the interviewees, understanding what can be expected from an interview of a person at a specific level, how to verify the information received from an interview, and, most important, understanding the perspective of the person being interviewed.

Most analysis projects have a user liaison assigned to the analysis team. It is this person's function to introduce the analyst to those being interviewed, to provide background information, and to interpret (or translate) the information which is obtained from the interviews. This person usually has the additional role of assisting the analyst in choosing those to be interviewed, scheduling the interviews themselves, and in some cases attending the interviews.

Under normal conditions, the analyst will have access to all people in the user area, although normally there is no need to interview them all. This is especially true if the user area is very large.

Generally speaking, the list of those to be interviewed can be divided into three sections:

The following are some guidelines for the analyst as to who to interview, when to interview them, what their perspective is, and what to expect from the interview (the goal of the interview itself).

The analyst can expect that the information received here will be general in nature. However, the manager will be able to define fairly accurately the business objectives of the project, the functions for which support is needed, any perceived problems which require attention, the time frame within which the project is expected to be completed, and the constraints, both business and financial, which apply. This manager can also suggest persons to interview, areas to concentrate on, and other sources of information. This manager should also be able to provide the enterprise perspective which is vital to the analyst's understanding.

For each area within his or her control, the manager should be able to give the analyst an organization chart which indicates the structure of the area, the number of people within it, and an overview of its function. These charts should be used to select the names of individuals to be interviewed: the area manager, interviewees recommended by the manager, and, if necessary, alternative contacts in each area.

The analyst should not expect great levels of detail about the individual activities of the area nor about the individual tasks which are performed, much less how they are performed.

Regardless of any other information acquired, it is this senior manager who will benefit most from the project, who in most cases is funding the project itself, and who will in all probability have the final sign-off on the completed work. It is vital, therefore, to have a clear undestanding of what is expected by this person.

It may also be found that the actual scope of the project, or the problem, is larger than originally defined and that the sources of the problem are in areas other than those which are experiencing the symptoms. For this reason it is usually a good idea to request and receive explicit permission from the senior manager to interview each of the second-line managers.

The senior manager should also be asked to explain to them the scope of the project, its intent, and that it may be necessary to interview some of their subordinates as the project progresses even though they are not directly involved (initially) in the project.

In many cases, people move from function to function, or at least from activity to activity during their employment by the firm. Many of these people may have more knowledge about the area under analysis than the current incumbents.

In many cases the managers themselves will have been promoted through the ranks, and will retain, if not current information about the area activities, at least some of the historical perspective as to how and why the area performs some of its activities and how they have changed over the years. In addition they can provide additional detail as to any problems, the reasons for those problems, and suggested ways to resolve them.

The managers at the various levels may also be able to clarify the statements made by their immediate superiors. The analyst will find that each person has a different perspective on an area, a perspective which reflects the individual's responsibilities and authorities. Each individual will also be able to provide a more detailed perspective on the interactions between different areas.

One of the things the analyst should be doing constantly during these interviews is verifying and cross-checking the information received. This cross-checking should be done in an objective manner and should not violate any information given in confidence. The objective is not to place blame or point fingers but to ensure that the information is correct. Where discrepancies arise between the information received from different managers, it may be necessary to verify the original information or seek a third source.

Generally, the analyst will want to interview at least one person from each specific task or activity area. In some cases it may be necessary to interview more than one person. Each person interviewed will in all probability refer to something received from or passed to another person or area. The analyst must verify that both individuals agree on the identity of the materials they are passing to each other and that both agree on the content of the transferred material. The understanding of the operations level personnel as to their specific duties, functions, and activities must match that of their immediate managers. Any discrepancies in this area must be resolved by the analyst.

The Need for Documentation

Everyone talks about the weather but no one can do anything about it. In the case of documentation, everyone talks about it but few do it; however, unlike the weather, most people can document, and document effectively.

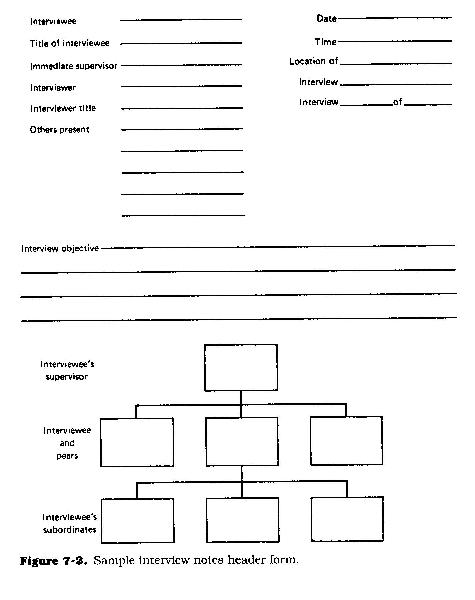

Documentation, however painful and tedious it may seem, is one of the most critical tasks of analysis. The documentation produced as a result of the analytical interviews, the analyst's observations and research, and ultimately, the total analysis phase of the project serves a number of purposes.

Permanence. The need for documentation is rooted in semantics and human memory. Verbal communications are both transitory and subject to interpretation. The average person has a language working set of about 500 to 1000 words. The written working set, by contrast, is much larger, perhaps by as much as an order of magnitude. Verbal communication is augmented by inflection, body language, and by a process of feedback and interaction, all of which serve to clarify the ambiguous, the ill-defined, and ill-understood. Human memory is imperfect. Words communicated verbally can only be recalled and examined with difficulty, if at all.

Precision and recall. A written document is more precise and may be reviewed repeatedly until understanding is achieved. It has the added advantage that small changes can be made to it without having to restate the entire premise or thought. Additionally, once an idea is written down, it may be recalled at will exactly as first presented and may be completed by someone other than the original author, or authors. Because there is little feedback from the written word, one can only take issue with misstatements of fact or with ambiguous wording. If it isn't written down, it isn't there.

Graphics. Documentation usually includes both a narrative portion and an illustration portion. These illustrations serve to amplify and enhance the narrative. One picture can be worth many thousands of words, if properly drawn. The graphics of the analytical documentation, whether it employs simple flowcharts, HIPO diagrams, data flow diagrams, or powerful modeling techniques such as those based upon the entity-relationship-attribute approach, presents the user and the analyst with a way to walk through the picture developed from the analysis, and ultimately walk through the design developed from the analysis. These walk-through sessions enable both to understand the environment and to detect any ambiguities and anomalies. Illustrations have the added advantage that they can be viewed in their entirety, whereas narrative may only be viewed in fragments.

Functions of Documentation

Documentation serves to clarify understanding, and perhaps most important, it provides the audit trail of the analyst. That is, it creates the records which can be referred to at some later date and which serve as the basis for future work and decisions.

Good documentation precludes the need to return to the interviewee for a repetition of ground previously covered. Good documentation can be reviewed over and over until adequate understanding is achieved.

Documentation is tedious and sometimes boring. But it is also vital. Good documentation allows other analysts and the analyst's successors to pick up where the first left off, should he or she be reassigned. Documentation is necessary if the next project phases are to be successful, since they are predicated on the results of the analysis. To a very real extent, analytical documentation provides the road maps for the remainder of the project. If the maps are faulty, or incomplete, the succeeding teams may wind up in a swamp, or worse, in quicksand.

Most important, the finalized documentation serves as a contract between the user and the data processing developer. In it the analyst has described the user's environment, the analyst's understanding of the user's needs and requirements, and with the proposal for a future environment, the analyst's description of the system to be designed and built by the developers. With the user's sign-off, or approval of these documents, a contract is created between the two. Barring unforeseen changes in the business environment, the problems described in the documentation will be rectified and the environment proposed will be the one built and installed for the user.

The document becomes, in effect, a statement of the work to be performed. The time to modify and change it is before the work begins; afterward it may be too late. From the developer's perspective, any post sign-off changes may require a re-negotiation of either time frames, costs, or resources. From the user's perspective, the design is what is contracted for and what he or she is paying for. If the final product does not conform to the proposal, then it is up to the developer to rework the product until the user is satisfied.

Documenting the Interview

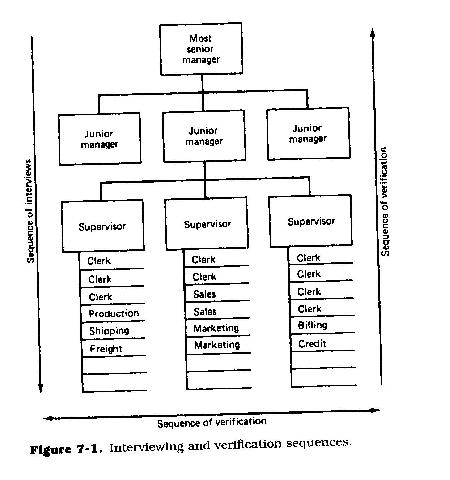

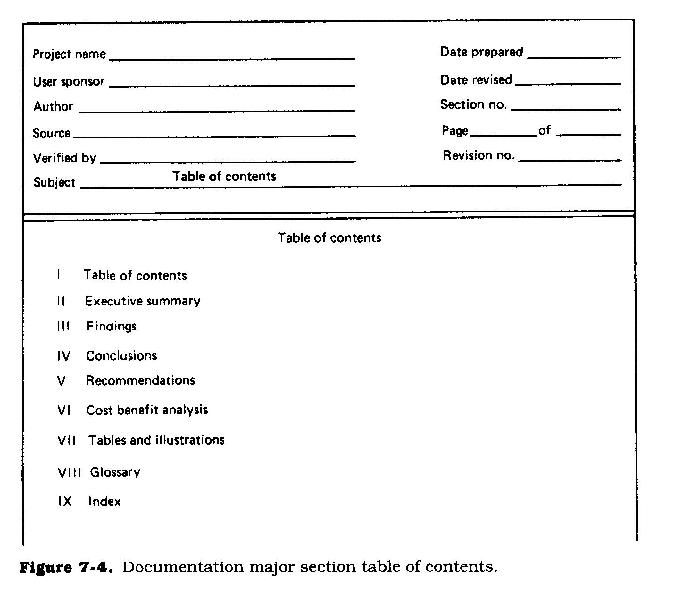

The interview is not complete until it has been documented. See Figure 7.2 for a header form for sample interview notes. The documentation of the interview need not be a verbatim transcript of what was said but should cover the following items.

Dos and Don'ts of Documentation

Report Format Style Guidelines

The appearance and readability of documentation can be greatly enhanced by following these guidelines.

Use a consistent outline format that makes it easy for the reader to determine the current location the document structure. Although mixed numeric and alpha outlining is frequently used, in can be very confusing, especially if the full item parentage is not used. Numeric outlining, on the other hand makes it easy for the reader to determine current location. For example,

If it becomes necessary to itemize under any heading use lower case roman numerals.

i)

ii)

iii)

iv)

An indentation should always have more than one item.

Every outlined section should always have a boldfaced heading.

Do not start a paragraph with a number or a single letter.

Avoid the use of bullets or special marks in final reports--they give the impression that the report is still a summary

Make sure that all words are properly spelled and that proper grammar is used. Nothing can be more detrimental to a report than improper grammar or word usage. Avoid slang, technical jargon, and idiom where possible.

The following are general stylistic considerations which apply.

Non-Interview Data Gathering Methods

In today’s business environment, when almost all office workers are provided with a personal computer, and almost all managers have one as well, it has become increasingly necessary to extend the scope of the data gathering process to a larger portion of the workforce, in some cases it has become necessary to gather data from all employees in a given areas, or even in extreme cases throughout the firm. Obviously in these cases interviewing everyone is impractical.

There are several data gathering methods which are used in these cases:

Phone Interviews – These are used to gather non-sensitive yes or no types of answers to highly focused questions.

Characteristics:

Table 7.1 Advantages and Disadvantages of Phone Interviews

|

Advantages |

Disadvantages |

To Be Effective |

|

The interviewer can clarify questions if answers are not understood |

There is no opportunity to establish a rapport with the interviewee |

Develop a short, concise, clear script |

|

It is the fastest method to collect information and has a better response rate that mail surveys |

The scope of the survey is necessarily limited |

Test the questions to be asked with project team members and several potential respondents |

|

It is the least expensive type if interview |

Respondents tire quickly during the interview |

Contact the respondent before the interview and gain agreement to the interview |

|

It is difficult to schedule phone interviews in advance |

Set a time for the interview with the respondent in advance |

|

|

It is difficult getting return calls |

Forward a questionnaire to the respondent prior to the time of the interview containing brief background information on the project and all questions to be asked. This will help them to prepare for the actual interview. |

|

|

Try not to deviate from the pre-defined script |

Mail Surveys - These are used to gather broad quantifiable data from a large sample.

Characteristics:

Table 7.2 Advanages and Disadvantages of Mail Surveys

|

Advantages |

Disadvantages |

To Be Effective |

|

Can be answered at the interviewee’s own time and place |

There is no control over who will respond |

Develop a questionnaire with short, concise, clear questions, not susceptible to ambiguous answers |

|

The answers are not as susceptible to bias |

There is no rapport with the interviewee |

Test the questions to be asked with project team members and several potential respondents |

|

It can reach more people |

30% to 40% response rate is considered very good, with the typical response rate being closer to 10% |

Contact the respondent before and after the survey is distributed |

|

It is easier to administer and easier to compile |

There is a lower probability of getting detailed information |

Make the survey quick and easy to complete (try for a survey takes no more than 30 minutes to complete) |

|

There is no opportunity to clarify ambiguous answers |

Include a postpaid envelop with the questionnaire |

|

|

Ask for permission to follow up on any answers that are unclear and ask for a contact number and best time for contact |

Focus Groups – These are used to obtain different reactions to one topic. Focus groups generate synergy provided the participants are at the same technical or organizational level.

Characteristics:

Table 7.3 Advantages and Disadvantages of Focus Groups

|

Advantages |

Disadvantages |

To Be Effective |

|

The interviewer can clarify questions if answers are not understood |

The group can easily get off the topic if not facilitated properly |

Distribute the agenda well before the meeting |

|

It can be used to gather data from multiple sources concurrently |

Ask the participants to introduce themselves. |

|

|

The group interaction provides an immediate validation of the data gathered |

Give the participants a concise background of the project, tell them why they were invited and define the goals of the meeting |

|

|

It is difficult to schedule phone interviews in advance |

Start with easy topics and questions and work toward the difficult ones. |

|

|

It is difficult getting return calls |

Document the proceedings and forward a copy of the proceedings (see next item) to all participants |

|

|

Guarantee anonymity to any participant of requested |

Site Visits – These are used to obtain first-hand understanding of the processes, activities, physical environment and working conditions

Characteristics:

Table 7.4 Advantages and Disadvantages of Site Visits

|

Advantages |

Disadvantages |

To Be Effective |

|

Improves interviewer understanding of working project environment |

Untrained or inexperienced team members may use it as an opportunity for a field trip rather than as a data gathering exercise. |

Prepare carefully |

|

Obtain information which may not have been shared during the interviews |

Number of sites that can be visited are limited |

Make sure there is a clear agenda and that all participants are aware of the schedule |

|

Validates data gathered from other sources |

Time and resource consuming |

Verify all appointments in advance |

|

Must be carefully scheduled well in advance |

Forward brief background information on the project and all questions to be asked to the interviewee in advance. This will help them to prepare for the actual interview |

|

|

Opportunity for disrupted schedule or distractions is high |

Joint Applications Design (JAD) and Joint Requirements Analysis (JRA)

In recent years the traditional practice of sending an individual analyst or even a team of analysts out to interview the users has been supplemented by the practice of bringing the users together as a group, guided by a facilitator, to analyze business functions, processes, activities and data as a joint effort. This is similar in nature to a focus group but the JAD process usually last much longer, sometimes for several weeks (if full-time) or months (if part-time)

This process of Joint Application Design is predicated on the assumption that user experts, under the guidance of a facilitator, can identify the functional requirements and business processes in sufficient detail to develop a comprehensive set of system requirements and design specifications.

JAD sessions are usually composed of several user experts, a facilitator, a scribe and sometimes an assistant. The facilitator works from an agenda and normally doesn’t participate in the requirements or design discussions, but seeks instead to guide the users toward their goal, keep the user discussions from deviating onto tangents and asking questions that move the discussion along. The facilitator will record the information presented by the users on flip charts and wall boards and ask clarifying and focusing questions. The scribe will record the information on the computer if possible, or transcribe the information from the wall charts after the formal session ends.

JAD and JRA sessions start with identification of mission and goal statements, and proceed to identification of business requirements. These requirements come in the form of data requirements (normally organized by business entity which are identified while the work progresses) and business processing requirements or business rules. These sessions must identify what must be done, and why it must be done, but should ignore how the work gets done.. Since the participants are functional experts, who are well versed in both what and how, it is sometimes difficult to separate the what form the how. Perhaps most difficult to ascertain is why these activities must be done. Often the reason why actions are taken is lost in the past, or the justification is “because the procedures say to do it that way” or worse “because we have always don it that way.”

Most JAD/JRA sessions are supported by automated products such as a CASE tool which allow the graphic and textual information to be captured and formalized as it is developed.

The following items should be available for a successful JAD/JRA session:

The success of these sessions is dependent in large part on the skill and experience of the facilitator. User experts tend to have a highly focused and parochial view of their business processes and may not see connections that might be obvious to an objective outsider. The facilitator should know enough to ask probing questions, and be able to resolve conflicts between users over the statements of requirements or the value of business processes.

Each participant should be prepared to send as much time as is necessary to complete the task. Most JAD sessions will run for five to fifteen full days, depending on the complexity of the subject area under analysis, the degree of understanding of the subject area by the participants and the degree of change that is necessary. Some subject matter experts may spend only a few days with the JAD team, others should be prepared to spend the entire time.

Prototyping

A definition

A prototype is a model on which later stages or development is based or judged. Prototypes are usually primitive forms used to evaluate a design. Prototypes may or may not actually work.

Although any model can be considered a prototype, the term is most commonly applied to screen based mock-ups of the screen portion of proposed data entry, query or reporting applications. Typically prototypes do not have any business or application processing logic associated with. That is the user can see the screen as it will appear in the final product but aside from simulating the sequence of date being entered, there is normally no other response.

Most CASE tools provide facilities to define and place data on a screen, and to simulate the pull-down menu, pop-up information windows, scrolling of data and screen to screen movement (the transfer under user control from one data screen to another).

Many stand-alone tools and several developer tool kits which also provide this kind of capability. Prototype generators may also be called screen painters

The advantages of Prototyping:

The disadvantages of prototyping are:

A Professional's Guide to Systems Analysis, Second Edition

Written by Martin E. Modell

Copyright © 2007 Martin E. Modell

All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Except as permitted under United States Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means, or stored in a data base or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the author.